Lab ratings tell only part of the story. Real sites face summer heat, thin air at high elevations, dust, and tight enclosures. Inverter derating under these conditions can trim available AC power and reduce efficiency. This piece shows practical ways to size inverters for reality, with heat derating, altitude derating, and inverter efficiency under extreme conditions front and center.

Why derating matters more than the datasheet headline

AC nameplate often assumes standard test conditions: sea level, 25–40°C ambient, free airflow. In practice, many sites hit 45–55°C surfaces and 1500–3500 m elevations. Those two factors alone can take a 100 kW inverter down to 70–90 kW during the hours that matter.

Several authorities highlight the need to plan for field conditions. According to IRENA, climate and siting drive renewable system performance and reliability, so designs should reflect local stressors. The IEA notes that real-world PV yields depend on ambient corrections and operating profiles, not just peak efficiency. The EIA shows that heat waves increase electricity demand and stress equipment, which amplifies the value of robust thermal design on the supply side.

Derating fundamentals you can use

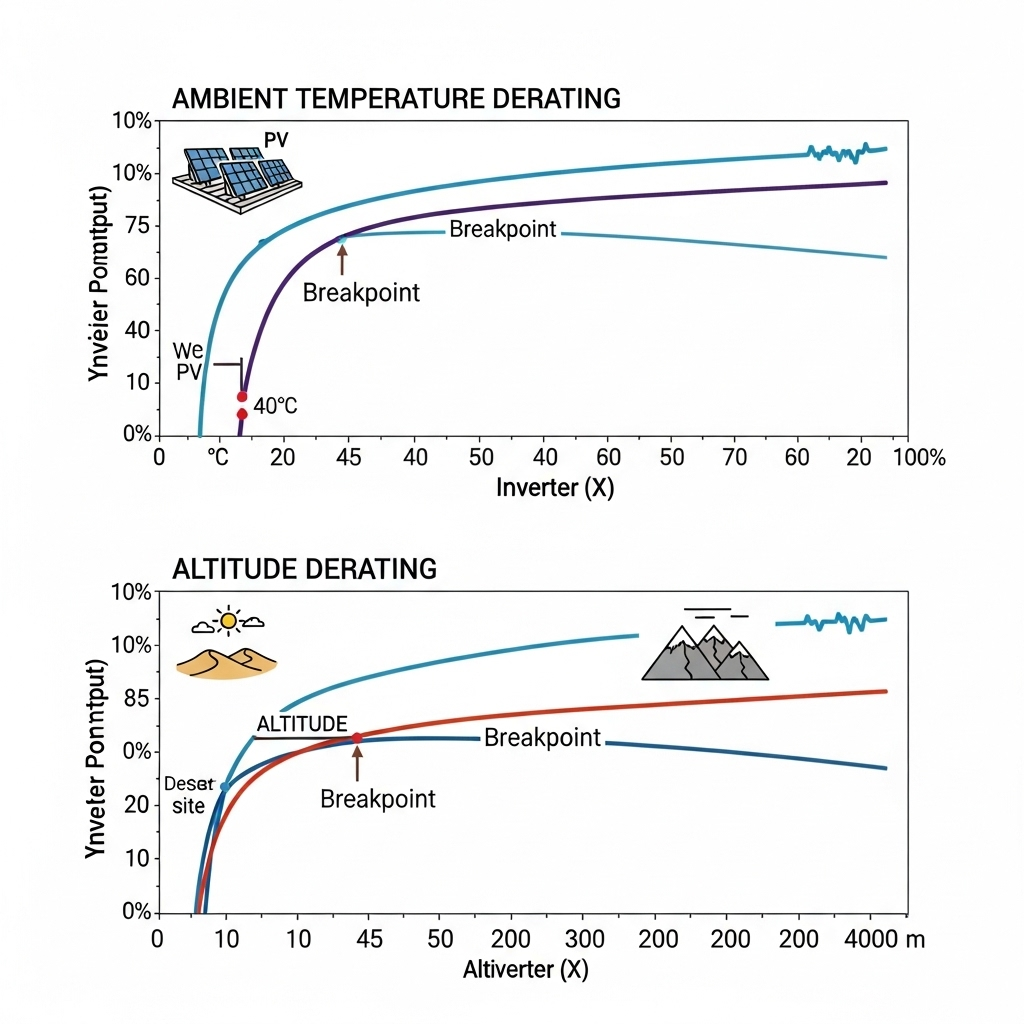

Heat derating: typical patterns

Most large string and central inverters hold full power up to a thermal knee, often 40–45°C ambient. Above the knee, firmware reduces output to protect semiconductors and magnetics. While exact curves vary, a common pattern looks like this:

- Up to 40°C: 100% available AC power

- 45°C: 95–100%

- 50°C: 80–90%

- 55°C: 65–80%

These ranges reflect typical datasheet curves. Always use the vendor’s published graph for final design. Still, these benchmarks help you sanity-check a model early.

Altitude derating: thin air, less cooling

Air density drops with elevation, so convective cooling weakens and dielectric clearances face higher stress. A frequent rule in datasheets is a small power reduction above a threshold altitude. Typical guidance:

- 0–2000 m: 100% rated

- 2000–3000 m: reduce 0.5–1.0% per 100 m

- 3000–4000 m: steeper reduction possible, check specific model

As a rough value, air density at 2000 m is about 80% of sea level. That alone explains why heat derating starts earlier on a mountain site.

A quick sizing formula

You can combine effects with a simple multiplicative model for first-pass checks:

Effective AC power ≈ Rated AC × f_temp × f_alt × f_PF

- f_temp: temperature factor from the curve (for example, 0.85 at 50°C)

- f_alt: altitude factor (for example, 0.95 at 2500 m if 1%/100 m above 2000 m)

- f_PF: power factor allowance (for example, 0.95 if reactive support is required)

This is not a substitute for a final thermal study, but it avoids surprises.

Worked examples with realistic conditions

| Site | Ambient hot-hour | Elevation | Assumed f_temp | Assumed f_alt | PF headroom | Effective factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phoenix roof | 50°C | 350 m | 0.85 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.81 |

| Denver ground | 38°C | 1600 m | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.93 |

| La Paz site | 30°C | 3600 m | 1.00 | 0.88 | 0.95 | 0.84 |

Interpretation for a 100 kWac rating:

- Phoenix roof: ~81 kW during the hottest hour

- Denver ground: ~93 kW during hot afternoons

- La Paz site: ~84 kW despite mild temperature, due to elevation

These examples mirror the patterns installers report in hot, high sites. For mission-critical applications and microgrids, the U.S. DOE SETO microgrids success story shows how grid-forming inverters restored a testbed after a blackout. That type of resilience relies on adequate thermal margins as well.

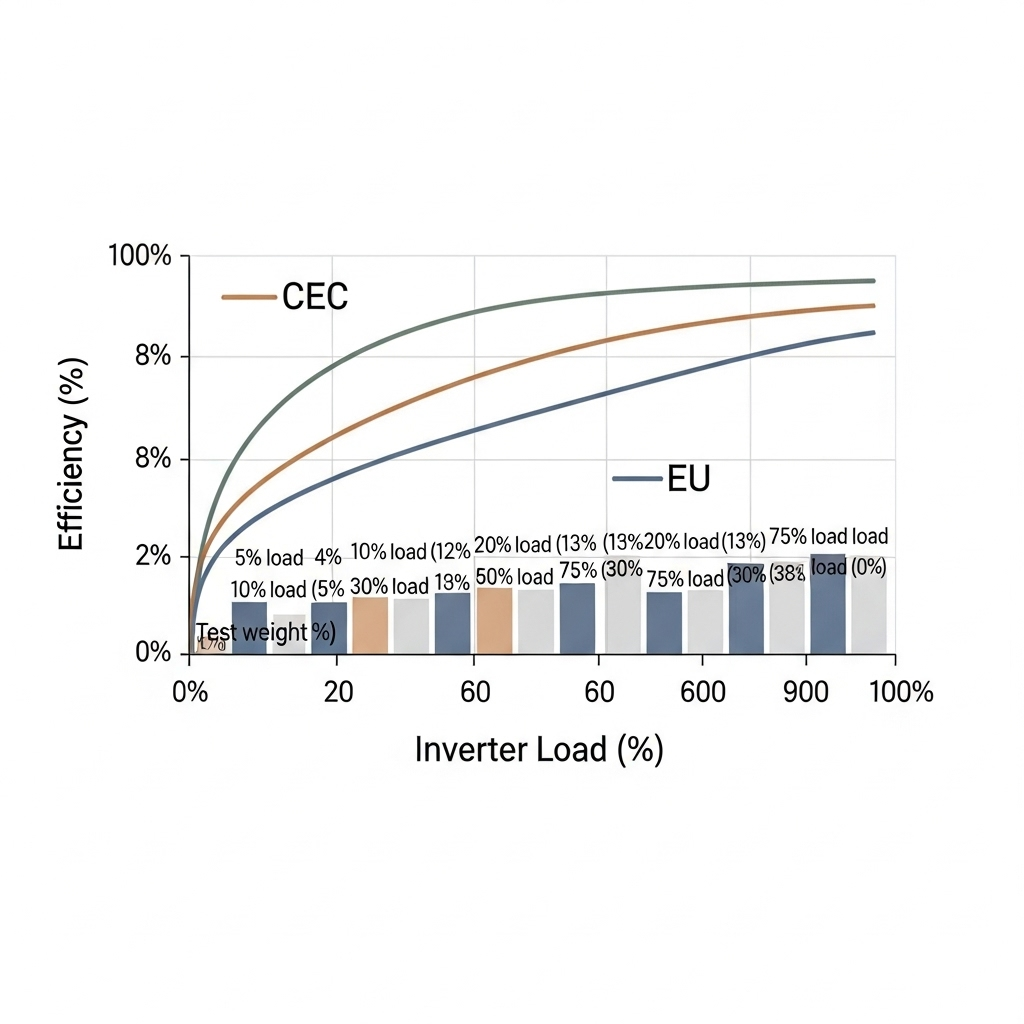

Inverter efficiency under extreme conditions

Peak efficiency at 25°C says little about hot-hour behavior at part load. Expect small decreases in conversion efficiency as temperature rises. In addition, operating at curtailed power can shift the working point off the sweet spot. To ground this:

- Energy.gov’s power electronics success story highlights how topology and wiring can lift module-level performance. The same principle applies inside larger inverters: thermal design and control strategies protect efficiency.

- IEA analysis often separates laboratory metrics from field-weighted performance. Use weighted efficiencies and local climate bins to estimate seasonal yields, then overlay derating windows.

Designers who must hit a kWh target should simulate hourly ambient bins and apply the vendor’s derating map rather than a single annual factor. That keeps yield forecasts honest.

Practical sizing steps: from array to AC reality

Step 1: Define site stressors

- Identify 99th-percentile ambient temperature at inverter location (shaded vs rooftop can differ by 5–10°C)

- Confirm elevation in meters

- Check enclosure type and airflow (indoor with HVAC, outdoor free-air, cabinet with filters)

Step 2: Translate to power factors

- Extract f_temp from the inverter’s published curve at the hot-hour ambient

- Extract f_alt from the altitude note (or ask the manufacturer for a dedicated curve)

- Add PF/kVAR headroom based on interconnection rules

Step 3: Select the AC rating

- Compute minimum AC rating = required hot-hour AC / (f_temp × f_alt × f_PF)

- Round up to the nearest catalog size and apply a modest design margin (5–10%)

- Re-check breaker and conductor sizing since higher kVA choices raise current

Step 4: Consider hybrid strategies

Storage can reduce thermal stress by shaving peaks and evening out inverter loading. As summarized in this solar and storage performance reference, lithium iron phosphate systems operate safely across a broad temperature band and support cycling that aligns with daily peaks. Shifting a few kW during the hottest hour can keep an inverter inside its full-power envelope, cutting thermal throttling without oversizing the AC hardware.

Cooling, placement, and BOS details that protect yield

- Mount in shade. Direct sun can raise skin temperature 10–20°C above ambient, pushing you past the thermal knee.

- Respect clearances. Maintain manufacturer airflow gaps on all sides; avoid stacked arrays of gear where hot exhaust recirculates.

- Filter and clean. Dust blankets heatsinks and reduces convective transfer. Schedule maintenance during peak heat season.

- Consider HVAC for equipment rooms in hot climates. A small split unit can pay for itself by avoiding throttling.

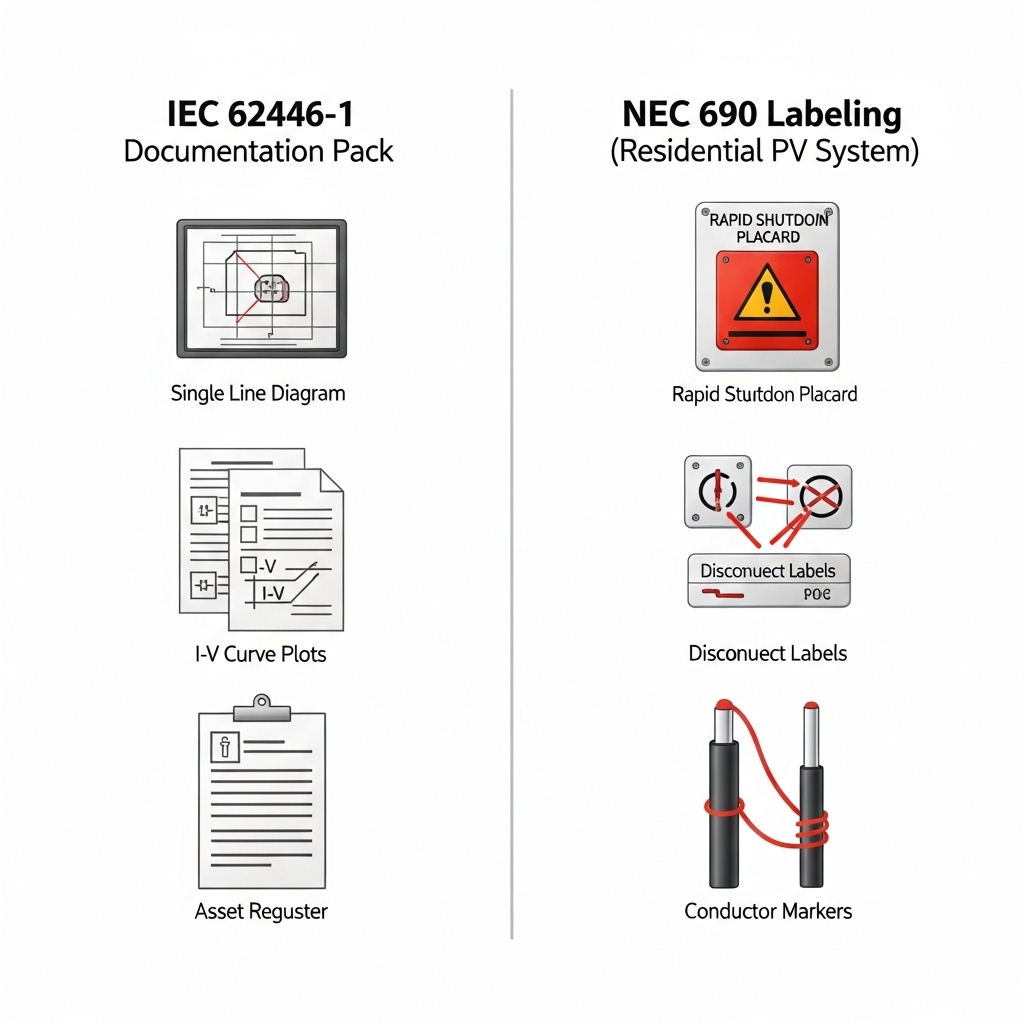

- Cabling and breakers. High temperatures reduce ampacity; check NEC/IEC tables for temperature corrections so the BOS does not become the bottleneck.

Worked sizing check: three 100 kWdc arrays, three sites

Assume ILR 1.2, required hot-hour AC export 90 kW, PF 0.98. We compare three siting cases.

| Case | Ambient | Elevation | f_temp | f_alt | f_PF | Needed AC rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shaded desert pad | 45°C | 500 m | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 90/(0.95×1.00×0.98)=96.6 kW |

| Rooftop urban | 52°C | 200 m | 0.82 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 90/(0.82×1.00×0.98)=111.9 kW |

| High plateau | 35°C | 3000 m | 0.99 | 0.90 | 0.98 | 90/(0.99×0.90×0.98)=102.0 kW |

Result: the rooftop needs the biggest AC rating due to heat, not array size. The high plateau site also needs a step up due to altitude derating, even with modest temperatures.

Storage and hybrid inverters: keeping efficiency steady

Hybrid inverters paired with LFP storage can shift 5–20% of midday power into late afternoon. That reduces clipping and avoids hot-hour throttling on the AC side. The DOE microgrid story also shows the value of advanced control layers and grid-forming capability during disturbances, which favors inverter platforms designed with thermal and altitude margins.

For battery behavior across temperatures and charge/discharge profiles, see the consolidated data in this storage performance reference. Use those ranges to plan safe charge windows during heat waves so the hybrid stays efficient and within warranty limits.

Procurement checklist: specifications that prevent surprises

- Provide a heat and altitude envelope in the RFQ (for example, 52°C ambient, 2800 m elevation)

- Require published derating curves for temperature and altitude, plus PF/kVAR capability across the range

- Specify continuous operation at 50°C without fault (derating allowed), and surge behavior at site conditions

- Confirm efficiency map at hot ambient and at expected load points, not just peak number

- Ask for enclosure rating, airflow requirements, and service intervals for fans and filters

- Request a list of successful deployments in similar climates; corroborate with independent sources such as IRENA or IEA publications relevant to climate resilience

Key takeaways

Heat derating and altitude derating can trim AC headroom right where your yield and compliance need it most. Use worst-hour ambient, actual elevation, and PF requirements to back into the AC size. Consider hybrid storage to smooth peaks and keep inverters near their optimal operating point. Cross-check plans against authoritative data from IEA, IRENA, and EIA, and leverage field-tested insights from Energy.gov success stories.

FAQ

What is inverter derating?

It is the reduction of available AC output under certain conditions, usually high temperature, high altitude, restricted airflow, or power factor requirements. Vendors publish curves that show the percentage of rated power available at each condition.

How much power do I lose at altitude?

Many datasheets allow 100% up to around 2000 m, then reduce available power by roughly 0.5–1.0% per 100 m. Above 3000 m, some models apply steeper reductions. Always check the specific curve.

Does higher ambient always reduce efficiency?

Efficiency changes are usually modest, but heat can push the operating point into a less efficient region. The bigger impact is power limiting to protect components at high temperature.

Can storage eliminate thermal throttling?

Storage cannot change physics, but it can shift load and generation to cooler hours. That reduces peak inverter stress and improves effective AC output during hot periods, as summarized in this storage performance reference.

Should I always upsize the inverter?

Not always. First quantify f_temp, f_alt, and PF needs. In some cases, better placement, shading, or modest storage can achieve the goal without a larger AC frame size.

Do microgrids change the sizing approach?

The same derating math applies. Microgrids also need headroom for blackstart and islanded operation. The DOE microgrid case shows how robust inverters with adequate margins support resilient operation.

Disclaimer: Engineering guidance only. Site-specific codes and interconnection rules apply. This is not legal or investment advice.

Leave a comment

All comments are moderated before being published.

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.